Music in the Romantic Age was not abstract art. The personality, the individual, the word – the individuality of the artist always followed. Music allowed a personal, even intimate statement. This feature makes nineteenth-century artistic work remain in the circle of special interests of historians, the subject of research is not only a piece of art, but also the creative process that accompanied it. From the notes, letters and other non-musical sources today, we already know how Mozart composed his music (without patches and all clean) or Rossini wrote his (also fast and efficient).

From the sketches of music, however, it follows that not all composers created it easily. Schumann edited his compositions repeatedly with Bruckner notorious for his creative indecision. Compositional distractions did not bypass one of the greatest – Ludwig van Beethoven. His pieces matured slowly. "First, sketches were created, capturing the themes themselves in the most general outlines. He then wrote down his ideas wherever he went. When he ran out of music paper, he wrote on walls, doors, the menu at the inn at dinner" (Beethoven, Stefania Łobaczewska, p. 70). Regarding the secrets of the composer's workshop, we learn from fortunately preserved notes, shreds of motifs, phrases, repeatedly transformed and mutated. This was also the case with the overture to the opera Fidelio, which the composer had worked on four times, and we are not talking about minor corrections, but of deep quasi-surgical interventions. In this case his creative passion with a lot of self-criticism proves the great importance the composer attached to the shape of the opera overture. Was it only to be a loose reference to the main melodic themes of the piece, or rather a deeper expression of the main conflicts expressed in stage drama. Beethoven's choice was, of course, closer to the second concept. The overture was not to be an introduction to the opera, but rather, according to Beethoven, to be an integral part of it. “Leonora II” is a historical trace of the creative dilemmas of the composer, who was to write a total of four versions of the musical introduction to the opera. The most popular of them is probably "Leonora III", although the second version is also a very attractive piece, betraying some similarities to the dark climates of C.M. Weber’s overtures. Like other versions, "Leonora II" is connected with the content and atmosphere of the opera Fidelio, as evidenced by the use of the trumpet play from a distance to announce the arrival of the king who is to justly judge the imprisoned hero. Actually, all versions of "Leonor" today are pieces independent of the opera concert life, which is a proof of popularity. Well, when you are Beethoven, even the fruit of indecision is brilliant ...

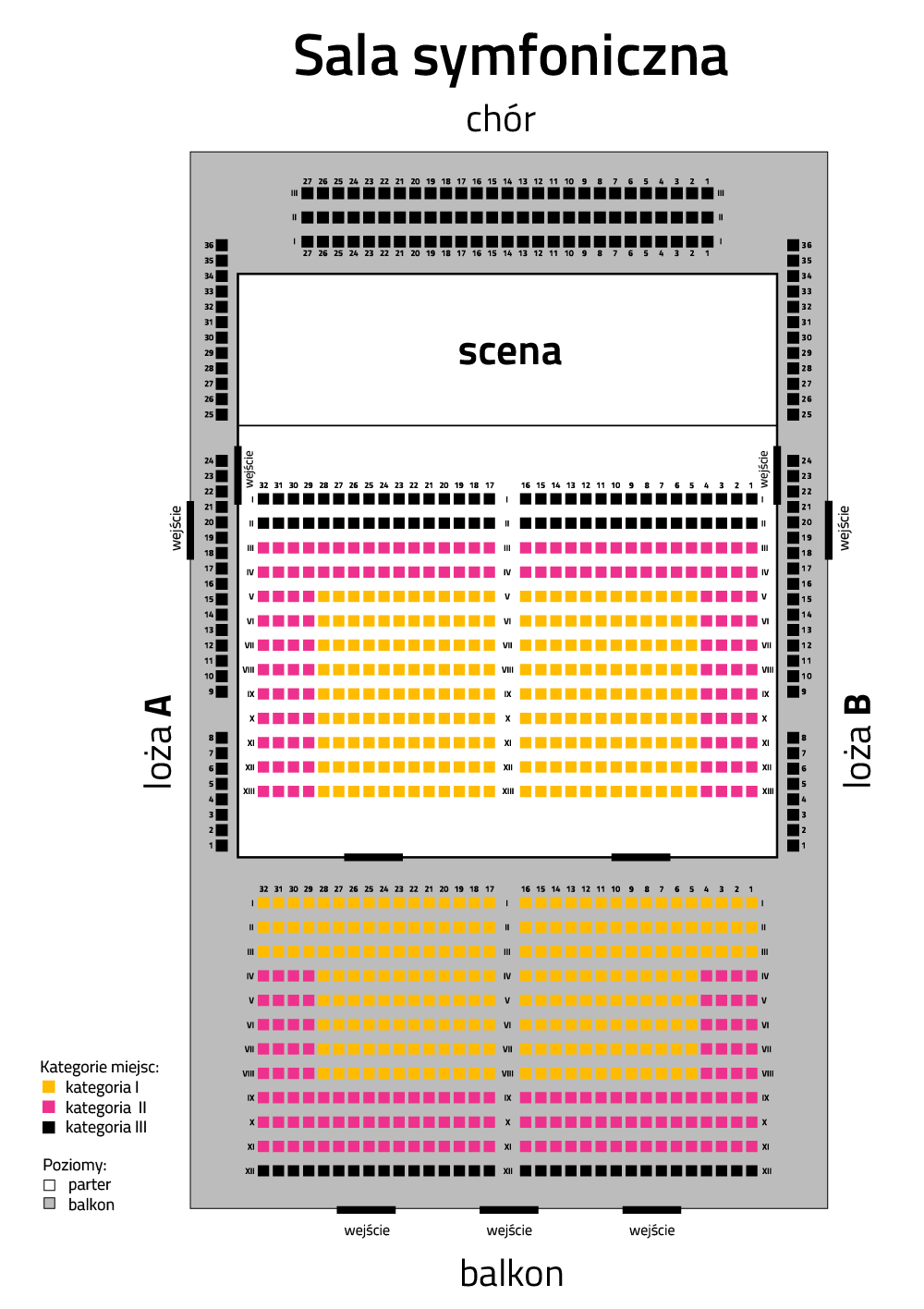

From the romantic world of Beethoven we will move, or perhaps we will make a great galactic jump, i.e. into the sound abstraction of Paweł Mykietyn's music. The concert for flute and orchestra was premiered on November 29, 2013 at the concert hall of the Artur Rubinstein Philharmonic in Łódź. The soloist for the Szczecin Philharmonic concert will be Łukasz Długosz, a graduate of renowned universities (Staatliche Hochschule für Musik in Freiburg, Hochschule für Musik und Theater in Munich). While "diplomas do not play on the stage", his list of awards at international competitions, and above all the number of concerts per year – 100!, testify to the high skills of this artist.

The composer of the concert, Paweł Mykietyn, is already a respected creator of contemporary music, for both philharmonic and festival stages, as well as for theater and film. In his latests compositions, the composer takes up a challenge against time in his music. In one interview he says: "I was always interested in the mathematical side of music, combinations and permutations. At first I used arithmetic progression, then geometric ones, which are more subtle." Critic Agnieszka Grzybowska, in relation to the flute concert, put it in the following way: "The action in the composition becomes thinner several times, Mykietyn tries to convince the listener that time is flexible and can be stretched a little. Formative meaning can be attributed to the measure of slowing down pace" (source:

pwm.com.pl). Is it not so that Beethoven himself did not define music as an open work, only perceiving the possibility in these variants of his works, and the contemporary artist has already incorporated this openness into the essence of the musical work?

From the considerations of the openness of the musical piece we will return to earth on Friday evening, and, as Jerzy Pilch would put it, in the strict sense. We will be helped in this by Ludwig van Beethoven’s Symphony no. 6 "Pastoral", a pioneering composition as for its own time (premiere in 1808). First of all, because it has five parts (not four as a classic symphony), secondly, because each part has a descriptive title.

* Awakening of cheerful feelings upon arrival in the countryside.

* Scene by the brook.

* Merry gathering of country folk.

* Thunder. Storm.

* Shepherd's song; cheerful and thankful feelings after the storm.

Although Beethoven wrote that this symphony caracteristica is more of a matter of feeling than of painting sounds, let's admit it is almost like some musical paintings. For example, an illustration of a bird singing or a thunderstorm. Beethoven had previously composed music for non-musical reasons, such as the symphony "Eroica" – a tribute to Napoleon or "The Wellington Victory." However, the idea of programming was expressed in Symphony No. 6 the best – the language of the sounds described here is the beauty of nature and the joyful feeling of being in contact with nature.

It would be a beautiful ending to state that nature was an ideal guide for the artist, and music scores are made without skewing, in a pure manner. Nothing could be further from the truth, the manuscript sketches for symphonies are more like the battle at Waterloo – thankfully a victorious battle.

------------------------------

Mikołaj Rykowski PhD

Musicologist and clarinetist, doctorate, and associate at the Department Music Theory at the Paderewski Academy of Music in Poznań. Author of a book and numerous articles devoted to the phenomenon of Harmoniemusik – the 18th-century practice of brass bands. Co-author of the scripts "Speaking concerts" and author of the spoken introductions to philharmonic concerts in Szczecin, Poznań, Bydgoszcz and Łódź.